Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has become one of the leading approaches to psychotherapy due to its strong research support and quick treatment timeline. Once clients learn how CBT works, they typically find that it can easily be applied to their own lives. It just makes sense.

For clients to use CBT effectively, they first need to have a strong understanding of the cognitive model. Psychoeducation will usually begin in the first or second session, and continue throughout treatment. Teaching the model can be a challenge, especially for therapists who haven't developed their own examples and scripts that they know are effective.

In this guide we will describe the CBT model and standard terms at a basic level, while sharing some tips for successfully imparting the knowledge to your clients. Our goal is for clients to be able to use this guide to learn the basics of CBT, while therapists can pick up some new examples, phrases, tools, and ideas to help them educate others.

The Cognitive Model

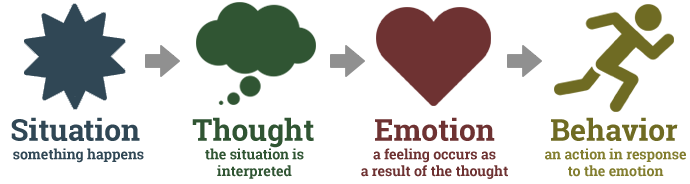

CBT is based on the idea that our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are constantly interacting and influencing one another. How we interpret or think about a situation determines how we feel about it, which then determines how we'll react.

The following example shows how this model might play out when two different people encounter the same situation:

| Situation: David and Jack receive poor grades on a math test. | |

|---|---|

| Jack | David |

| Thought: "If I was smarter I would've passed. I'm so stupid." | Thought: "I must've underestimated this test. I didn't study hard enough." |

| Emotion: Depressed and negative about future tests. | Emotion: Disappointed, but confident about the next test. |

| Behavior: Jake develops a negative opinion of himself and doesn't make adjustments to his test preparation, because he believes he is the problem. | Behavior: David isn't happy about his test score, but it doesn't affect his self-esteem. He makes a plan to study harder in the future. |

Now, let's take a closer look at each step of the CBT model, beginning with thought.

Thoughts

Our brains are constantly using thought to make interpretations about the world around us. When we see, hear, touch, smell, or taste something, our thoughts tell us what it all means. Without thought, we would be hopelessly lost.

Part of thought involves making assumptions about our surroundings. For example, if you see a stranger walking toward you with a weapon, you don't know that they're dangerous, but it's usually a safe bet. These sort of educated guesses play a clear role in our survival.

However, in some situations, these same sort of assumptions can be harmful. For example, someone might assume that anyone who walks toward them is a threat, even in a totally benign situation. Interestingly, people with mental illness such as depression, tend to have a higher number of unfounded negative thoughts, which we call irrational beliefs.

Because we're constantly encountering so much information, we can only pay attention to a small percentage of our thoughts at any given time. Many of our thoughts become automatic and occur outside of our awareness, as if they are a reflex. These are called automatic thoughts.

When a thought occurs automatically, we aren't able to assess it for accuracy, because we don't even know that it has occurred. We simply accept the thought as truth and move on. Sometimes, thoughts that are both irrational and automatic can lead us to experience a negative emotion without us ever becoming aware of why.

Emotions

As a result of our thoughts about a situation, we experience emotions. Look at this example to see how two people can feel very differently about the same situation, because of their thoughts:

| Situation: Jenny and Annie notice a man looking at them and walking in their direction on a crowded sidewalk. | |

|---|---|

| Jenny | Annie |

| Thought: "This guy seems fine—maybe he's just lost and needs directions." | Thought: "Why is this guy coming toward me? What does he want? He must be up to something." |

| Emotion: Happy / Friendly | Emotion: Scared / Nervous |

Some researchers believe that there are six basic emotions which can occur at varying levels of intensity and combinations to create the wide range of feelings we recognize. The basic emotions are love, joy, surprise, anger, sadness, and fear.

When experiencing emotions, our bodies undergo a number of physiological changes. For example, fear can lead the body to enter the fight-or-flight response which includes increased heart rate, sweating, and the tensing of muscles.

Emotions, much like thoughts, often go unnoticed (especially when they are less intense). However, even when emotions occur outside of our awareness, they still impact our thoughts and behaviors.

Try this exercise to see how thoughts and emotions can exist outside of our awareness: Take a second and notice how your hands feel at this very moment. Maybe you can feel the surface that they're resting on, the temperature of the room, or your computer mouse under your palm. Your hands are always experiencing some sensation, but it usually goes unnoticed. If you constantly paid attention to every little thing, your mind wouldn't be able to spend much time thinking about the things that are more important.

Now, imagine you accidentally touch a hot stove with your hand. Suddenly, all of your attention goes to your hand as you jerk it back toward your body. This same process occurs with emotions. If you live your life with a constant low level of anger, you'll probably start to ignore the feeling, even though it's still there. When someone cuts you off on the highway, your anger boils to the top and you can feel it.

It's important to understand that thoughts and emotions can occur outside of our awareness, yet still impact our behavior. This knowledge justifies why we need to practice identifying our thoughts and feelings if we want to change our behavior.

Behaviors

After we interpret a situation with our thoughts and experience an emotional reaction, we respond with a behavior. This whole process happens constantly, but it's usually mundane and not very noteworthy. For example, a low level of nervousness prevents us from crossing the road until it's clear of cars. The process works, and we make it across the street when it's safe.

Other times, the process doesn't work quite as well, and we begin to feel and behave in ways that hurt more than they help. Consider this situation, as experienced from two different people:

| Situation: Conor and Elliott both call a friend who doesn't answer the phone. | |

|---|---|

| Conor | Elliott |

| Thought: "They must be busy or they're just not in the mood to talk right now." | Thought: "They don't want to talk to me because I'm so boring and weird." |

| Emotion: Neutral / No Change | Emotion: Sad / Hurt |

| Behavior: Conor tries to call his friend again a few hours later. | Behavior: Elliott does not try to call his friend again and avoids them in the future. |

In the example above, we could guess that Elliott will have more difficulty maintaining healthy relationships if he continues to interpret neutral situations as if they are negative. The type of thoughts exhibited by Elliott are more common in people suffering from mental illness such as anxiety and depression.

Core Beliefs

The thoughts we have in any given situation are influenced by our core beliefs. These are beliefs that we hold at the center of who we are that describe the basic nature of the world. Some examples of common core beliefs are:

"I am unlovable."

"Everything turns out OK in the end."

"The world is a dangerous place."

Core beliefs are developed from a person's unique personal experiences. However, these beliefs aren't always accurate. For example, someone who was mistreated by a parent as a child might develop the belief that they are unlovable, when the problem was actually their parent.

Imagine your core beliefs are like a filter that each thought must pass through. If someone has the core belief that they are unlovable, each of their thoughts will have to make sense in the context of that belief. The process might look something like this:

| Situation: Michelle and Audrey both call a friend who does not answer the phone. | |

|---|---|

| Michelle | Audrey |

| Core Belief: I believe that I'm unlovable, so how does this situation make sense with my belief? | Core Belief: I believe that I'm valuable, so how does this situation make sense with my belief? |

| Thought: "My friend didn't answer the phone because she doesn't like me." | Thought: "My friend didn't answer the phone because she's busy or just not in the mood to talk. She'll probably call back, and if not, I'll call her again tomorrow." |

Now, look at how the same negative core belief could impact even a positive situation:

| Situation: Michelle calls a friend who answers the phone and has a nice conversation. |

| Core Belief: I believe that I'm unlovable, so how does this situation make sense with my belief? |

| Thought: "My friend is really nice to put up with me. She's probably so annoyed by my phone calls. I should try not to bother her so much!" |

Cognitive Distortions

Unhealthy thinking patterns, called cognitive distortions, can lead to the reinforcement of negative thoughts and emotions. Cognitive distortions are common but irrational ways of thinking that can negatively impact emotions and behavior. Everyone experiences cognitive distortions to some degree, so don't be surprised if you can identify with a few of them.

- Magnification and Minimization: Exaggerating or minimizing the importance of events. One might believe their own achievements are unimportant, or that their mistakes are excessively important.

- Catastrophizing: Seeing only the worst possible outcomes of a situation.

- Overgeneralization: Making broad interpretations from a single event. "I felt awkward during my first job interview. I am always so awkward."

- Magical thinking: The belief that actions will influence unrelated situations. "I am a good person—Bad things shouldn't happen to me."

- Personalization: The belief that one is responsible for events outside of their own control. "My mother is always upset. It must be because I have not done enough to help her."

- Jumping to conclusions: Interpreting the meaning of a situation with little or no evidence.

- Mind reading: Interpreting the thoughts and beliefs of others without adequate evidence. "She wouldn't go on a date with me. She probably thinks I'm ugly."

- Fortune telling: The expectation that a situation will turn out badly without adequate evidence.

- Emotional reasoning: The assumption that emotions reflect the way things really are. "I feel like a bad friend, therefore I must be a bad friend."

- Disqualifying the positive: Recognizing only negative aspects of a situation while ignoring the positive. One might receive many compliments on an evaluation but focus on the single piece of criticism.

- "Should" statements: The belief that things always need to be a certain way. "I should never feel sad."

- All-or-nothing thinking: Thinking in absolutes such as "always", "never", or "every". "I never do a good job on my work."

Other CBT Resources

We've put together a short list of CBT worksheets, a video, and other resources that you might find helpful if you would like to continue learning about the cognitive model.